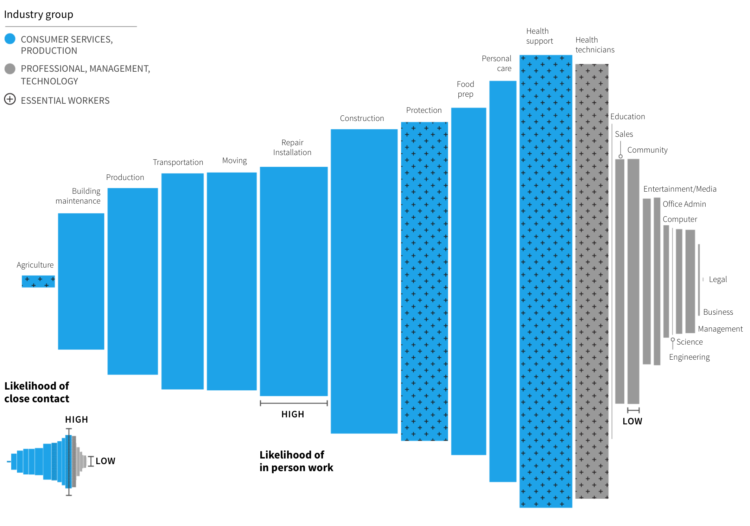

Some industries are more compatible with remote work than others. Jonathan I. Dingel and Brent Neiman at the University of Chicago estimated the scale of the differences. For Reuters, Sarah Slobin reports using a variable width bar chart to show likelihood of close contact with others against likelihood of in person work:

Professional, management and technology jobs run the gamut from accountants and architects to lawyers, insurance underwriters and web developers. This group is much more likely to retain the privilege of collecting a paycheck while working remotely, and is based in major metropolitan areas, like New York and Los Angeles.

See additional breakdowns by geography and job loss.

Tags: coronavirus, remote, Reuters, Sarah Slobin, work

"The Heartland Fund, and the foundations and consultants behind it, are trying to facilitate a turnaround of decades of philanthropic neglect of rural and suburban areas and small cities, starting with organizing and issue advocacy in the Midwest," Tate Williams reports for Inside Philanthropy. "Launched in 2018 with founding donors Wallace Global Fund and Franciscan Sisters of Mary, the new fund is backing work on economic justice, the environment and health. It also aims to find some common ground around these issues, and as a result, forge connections across cultural and political divides." It's not exactly a parachute philanthropy model, with urban outsiders trying to "fix" rural America; the steering committee is made of grassroots leaders from the communities Heartland supports.

Universities and health care, “eds and meds”, have been in a huge growth cycle over the last few decades. Many communities have been pinning their hopes on anchor institutions like a university or research hospital to retool their economies for the 21st century.

Yet the higher education industry is facing a convergence of several trends and forces that are threaten their future. At a minimum, schools need to be figuring out how to navigate these choppy waters ahead.

Here are six forces converging on colleges today and in the near future:

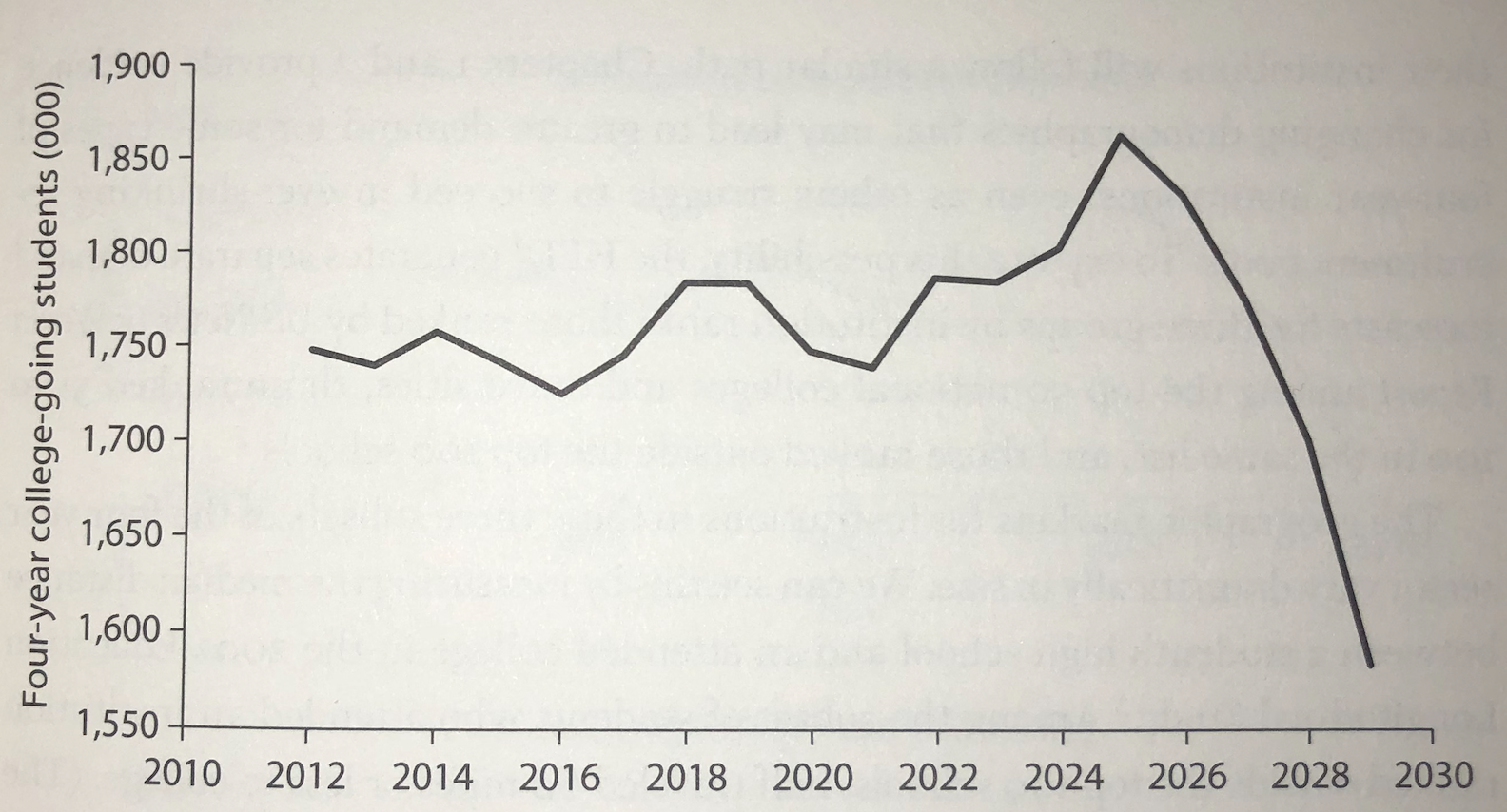

1. The number of college students will soon plunge. Professor Nathan Grawe, in his book Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education, built a model that projects the future demand for college. He found that starting in 2025, the number of college bound students is likely to decline substantially.

Figure 6.1 from Grawe’s book

The elite top 50 will continue to experience robust demand, but others won’t be so luck. As Grawe told the Chronicle of Higher Education:

The bottom line is there’s almost nothing that’s going to get us around the fact that, in the late 2020s, we should see really significant reductions in enrollment. If your strategy for this is to try to increase enrollments, the model suggests that that’s a bad idea.

Grawe has provided a large amount of grim data on his web site.

2. Tuition is soaring at rates far higher than inflation. This chart from Carpe Diem and AEI says it all. Tuition and textbooks have nearly tripled in price since 1997:

How much more can students and their parents take?

3. Student loan debt is soaring. Earlier this year New York magazine put together this astonishing chart of the growth of student loan debt relative to other kinds of loans:

![]()

CNBC reports that:

Over the last decade, college-loan balances in the United States have jumped more than $833 billion to reach an all-time high of $1.4 trillion, according to a recent report by Experian.

The average outstanding balance is now $34,144, up 62 percent over the last 10 years. In addition, the percentage of borrowers who owe $50,000 or more has tripled over the same time period, according to a separate report by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

The $1.4 trillion in student loans outstanding new exceeds total credit card debt and total auto loan debt. Some people now have over $1 million in student loan debt.

4. The over-education problem. One factor that’s seldom directly pointed out is the disconnect between the number of people who go to college, and the number who can plausibly cash in from a degree.

34.9% of people ages 25-34 have a bachelors degree or higher. This is probably a fair proxy for the share of younger people who will likely get degrees. But is 35% of the American public able to get a high paying job? Indicators are not.

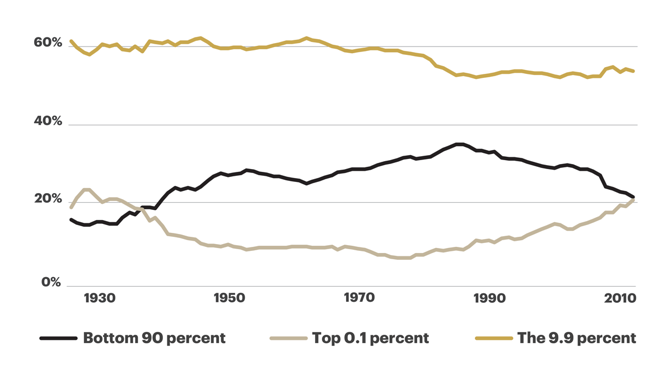

Much as been made of income inequality, the decline of the middle class, etc. Some share of the population, probably 20% or less, is reaping disproportionate rewards in the modern economy. Others have seen stagnating real wages. For example, the Atlantic just ran a cover story talking about the “9.9%” that had this chart showing the share of wealth held by the 0.1%, the 9.9%, and the bottom 90%:

Even if people in the next decile below the 9.9% are doing well, that still leaves a ton of people with degrees who don’t necessarily face great economic prospects.

They might instead end up changing diapers at a DC day care center. Washington put forth a mandate that day care workers have a college degree, which indicates they must believe there will be no shortage of takers.

Combine a degree that won’t grant access to the high wage economy with student loan debt and it’s a recipe for big problems for young people.

This is an area that deserves more study.

5. University inequality. It’s not just workers who face inequality, but schools themselves. The Wall Street Journal has been reporting on a potential shakeout among colleges, in which the higher end universities continue to do well, but those ranked nearer to the bottom are in trouble. In one article related to this divergence they note:

For generations, a swelling population of college-age students, rising enrollment rates and generous student loans helped all schools, even mediocre ones, to flourish. Those days are ending. According to an analysis of 20 years of freshman-enrollment data at 1,040 of the 1,052 schools listed in The Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education ranking, U.S. not-for-profit colleges and universities are segregating into winners and losers—with winners growing and expanding and losers seeing the first signs of a death spiral.

Similar they written that many non-selective small liberal arts may be in trouble.

6. MOOCs. The rise of online education, notably in the form of “massively open online courses” has yet to disrupt the higher education model, but with the factors above bearing down, there’s a huge financial incentive to make this work. Industry after industry have been radically restructured by technology innovation, and it’s reasonable to believe that the business model of higher education will one day end up on the receiving end.

7. The credentialing cartel. It’s widely understood that the primary value in a degree is having it. The degree itself is perceived as a key credential granting access to the job market. As Austen Allred put it, “Would you rather have a Princeton diploma without the Princeton education, or a Princeton education without a Princeton diploma?”

Universities are in effect a cartel who can levy an entrance toll to the professional job market. This may last for quite some time, or even strengthen, but there is again great value to be unlocked in breaking this cartel. The tech industry is a good example, where even famous companies have been founded by drop outs. If you are a great developer, it doesn’t matter what your credentials are. This has been one secret to that industry’s success.

None of these inevitably spells doom for colleges, and certainly not for any individual one. There is also a lot of nuance not captured in this short posting. But as a highlight of potentially disruptive forces, it shows that there is quite a collection of powerful disruptors and potential disrupters arrayed against the university environment. Savvy institutions should be working hard to get fit for the road ahead.

This piece originally appeared on Urbanophile.

Aaron M. Renn is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a contributing editor of City Journal, and an economic development columnist for Governing magazine. He focuses on ways to help America’s cities thrive in an ever more complex, competitive, globalized, and diverse twenty-first century. During Renn’s 15-year career in management and technology consulting, he was a partner at Accenture and held several technology strategy roles and directed multimillion-dollar global technology implementations. He has contributed to The Guardian, Forbes.com, and numerous other publications. Renn holds a B.S. from Indiana University, where he coauthored an early social-networking platform in 1991.

Photo: sach1tb (https://www.flickr.com/photos/sach1tb/274991658/) [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons